Thinking Activity on Tale of a Tab:

How far do you think Digression is necessary in the text “A Tale of a Tab? "

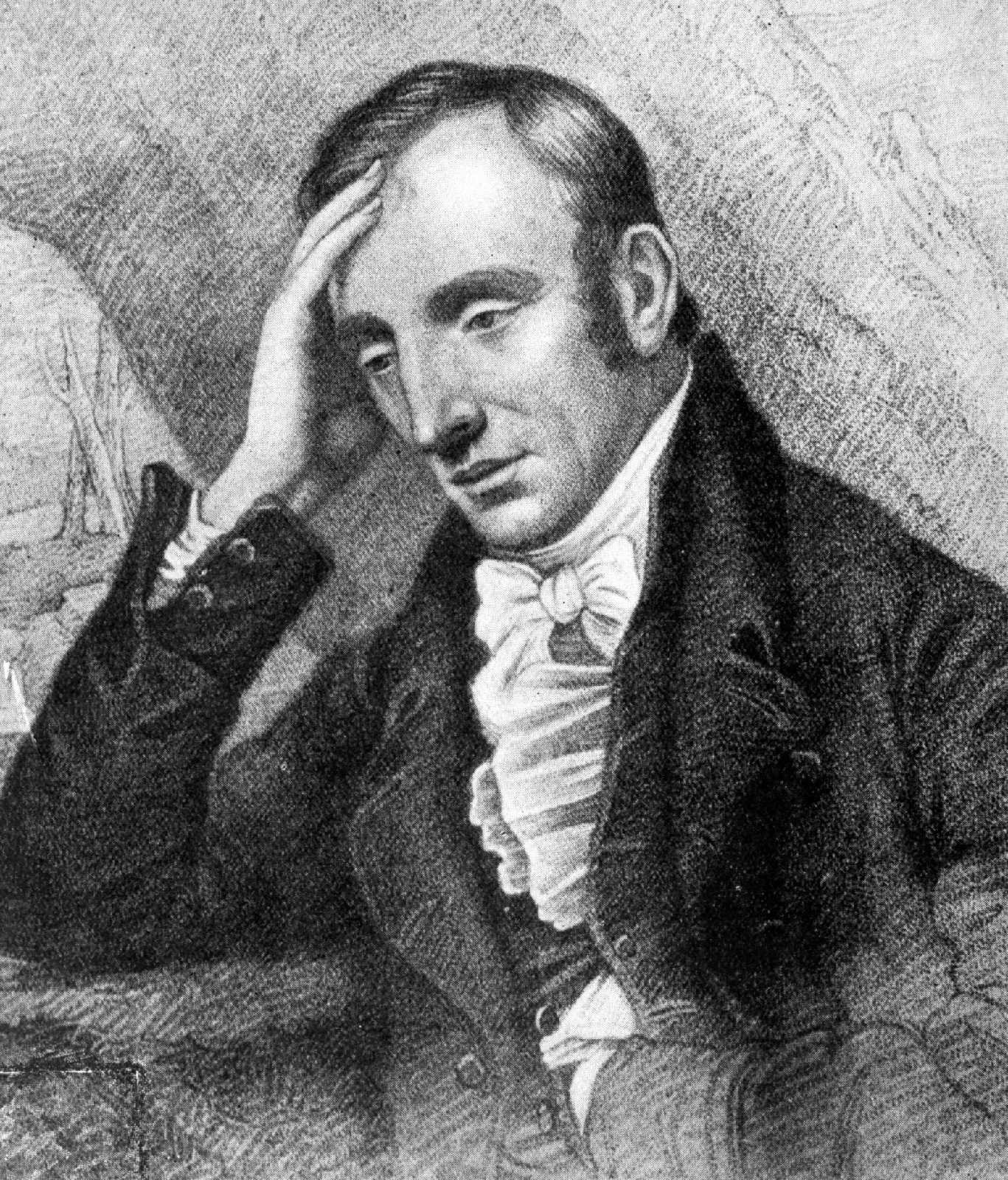

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet and cleric who Became Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin.

Swift is remembered for works such as Gulliver’s Travels, A Modest Proposal, A Journal to Stella, Drapier’s Letters, The Battle of the Books, An Argument Against Abolishing Christianity and A Tale of a Tub. He is regarded by the Encyclopaedia Britannica as the foremost prose satirist in the English language, and is less well known for his poetry. He originally published all of his works under pseudonyms – such as Lemuel Gulliver, Isaac Bickers Taff, MB Drapier – or anonymously. He is also known for being a master of two styles of satire, the Horatio and Juvenalian styles.

Summary

A Symbolic Gift

The main plot of A Tale of a Tub concerns three sons who inherit coats from their father with a command never to alter them. In youth, the brothers are committed to obeying their father's dying wish, but fashions change and they begin to feel left behind by polite society. They begin scrutinizing their father's will to see if there can be any justification for altering the coats after all. By twisting his words, they manage to rationalize the addition of decorative knots, then of gold lace, and eventually of numerous other decorations. Each time, they depart further and further from the obvious intent of their father's will, until eventually they are not even pretending to consult it.

Two Schisms

Eventually, the brothers move into a fine house together. The oldest, named Peter, becomes a tyrant who attempts to impose various absurd restrictions on the other two. He styles himself as an emperor and undertakes such extravagant projects as buying a continent and selling patent medicines. Tired of his bizarre and belligerent behavior, the two younger brothers obtain a copy of their father's will and are about to leave Peter but are instead kicked out of the house.

Martin, the middle brother, and Jack, the youngest, find lodging together and proceed to look over their father's will again. They are horrified to find how far they have strayed from their father's command regarding their coats. Both try to remove the various unlawful decorations from their coats—Martin patiently and methodically, Jack by ripping and tearing. Where the embroidery is so "close" that undoing it might damage the underlying material, Martin reluctantly leaves it in place. Jack, who is more motivated by his hatred of Peter than by respect for his late father, strips out every piece of fringe and embroidery, leaving the original coat in rags. A series of disagreements leads to a wider breach between the two brothers, and Jack goes off to seek his own lodgings.

Jack's Madness

Soon, rumours begin to spread that Jack has gone mad. He has founded a cult known as the Aeolists, or wind worshippers, whose rituals involve filling themselves with air and then grotesquely disgorging it by belching. He has become not only reliant upon, but obsessed with his copy of his father's will, which he uses as an umbrella, a nightcap, a bandage, and so forth. A braggart and a hypocrite, Jack picks fights and then claims that he has been persecuted for defending the Christian faith. Despite all this, and much to his own annoyance, Jack continues to resemble Peter so much that the two are often mistaken for one another. In the middle of a long catalog of Jack's odd behaviours, the story ends abruptly with "Desunt Nonnulla" ("Some things are missing").

The Digressions

Interspersed among the narrative chapters are several long "Digressions" in which Swift takes satirical aim at a variety of contemporary issues. Chapter 3, for example, is "A Digression Concerning Critics" in which Swift chides the younger generation of literary critics for forgetting their origins and presuming beyond their station. "A Digression in the Modern Kind" (Chapter 5) and "A Digression in Praise of Digressions" (Chapter 7) follow. Perhaps the most famous is "A Digression Concerning ... Madness" (Chapter 9), in which Swift mockingly proposes rescuing madmen from prisons and asylums and giving them positions in government. Together, the "Digression" chapters constitute approximately one-third of the book's entire running text.

From its opening (once past the prolegomena, which comprises the first three sections), the book is constructed like a layer cake, with Digression and Tale alternating. However, the digressions overwhelm the narrative, both in terms of the forcefulness and imaginativeness of writing and in terms of volume. Furthermore, after Chapter X (the commonly anthologized "Digression on Madness"), the labels for the sections are incorrect. Sections then called "Tale" are Digressions, and those called "Digression" are also Digressions.

A Tale of a Tub is an enormous parody with a number of smaller parodies within it. Many critics have followed Swift's biographer Irvin Ehrenpreis in arguing that there is no single, consistent narrator in the work. One difficulty with this position, however, is that if there is no single character posing as the author, then it is at least clear that nearly all of the "personae" employed by Swift for the parodies are so much alike that they function as a single identity. In general, whether we view the book as comprised of dozens of impersonations or a single one, Swift writes the Tale through the pose of a Modern or New Man. See the abridged discussion of the "Ancients and Moderns," below, for more on the nature of the "modern man" in Swift's day.

Swift's explanation for the title of the book is that the Ship of State was threatened by a whale (specifically, the Leviathan of Thomas Hobbes) and the new political societies (the Rota Club is mentioned), and his book is intended to be a tub that the sailors of state (the nobles and ministers of state) might toss over the side to divert the attention of the beast (those who questioned the government and its right to rule). Hobbes was highly controversial in the Restoration, but Swift's invocation of Hobbes might well be ironic. The narrative of the brothers is a faulty allegory, and Swift's narrator is either a madman or a fool. The book is not one that could occupy the Leviathan, or preserve the Ship of State, so Swift may be intensifying the dangers of Hobbes's critique rather than allaying them to provoke a more rational response.

The digressions individually frustrate readers who expect a clear purpose. Each digression has its own topic, and each is an essay on its particular sidelight. In his biography of Swift, Ehrenpreis argued that each digression is an impersonation of a different contemporary author. This is the "persona theory," which holds that the Tale is not one parody, but rather a series of parodies, arising out of chamber performance in the Temple household. Prior to Ehrenpreis, some critics had argued that the narrator of the Tale is a character, just as the narrator of a novel would be. Given the evidence of A. C. Elias about the acrimony of Swift's departure from the Temple household, evidence from Swift's Journal to Stella about how uninvolved in the Temple household Swift had been, and the number of repeated observations about himself by the Tale's author, it seems reasonable to propose that the digressions reflect a single type of man, if not a particular character.

In any case, the digressions are each readerly tests; each tests whether or not the reader is intelligent and skeptical enough to detect nonsense. Some, such as the discussion of ears or of wisdom being like a nut, a cream sherry, a cackling hen, etc., are outlandish and require a militantly aware and thoughtful reader. Each is a trick, and together they train the reader to sniff out bunk and to reject the unacceptable.

Digressions is necessary in this text.